Welcome Back! Maestro Filmworks is proud to open the fall season with a new monthly installment of Project Forte featuring Sofiya Abena Ballin (she/her) a compelling storyteller across multiple mediums, thriving right here in Philadelphia. Sofiya has evolved through creative writing and journalism, to production and editing, taking fierce care of the valuable human stories she excavates. Her project, Black History Untold, was born to print but has since blossomed into film, immersing the viewer into an intimate sharing of experience. Sofiya and her team gather raw perspectives tied to unsung ancestry, bringing the suppressed influences and inspirations of Black lives to us in a full, compelling and emotive way. These stories, as well as Sofiya’s own journey, create opportunities for empathy amongst us and refresh our understanding of how lush Black history is. She fought to see her vision fulfilled, overcoming outdated barriers that stifle the change we hope to make in our society. Work like this encourages new growth and conversation, which we know is a grand beginning not only for our communities but for Sofiya Ballin.

Welcome Back! Maestro Filmworks is proud to open the fall season with a new monthly installment of Project Forte featuring Sofiya Abena Ballin (she/her) a compelling storyteller across multiple mediums, thriving right here in Philadelphia. Sofiya has evolved through creative writing and journalism, to production and editing, taking fierce care of the valuable human stories she excavates. Her project, Black History Untold, was born to print but has since blossomed into film, immersing the viewer into an intimate sharing of experience. Sofiya and her team gather raw perspectives tied to unsung ancestry, bringing the suppressed influences and inspirations of Black lives to us in a full, compelling and emotive way. These stories, as well as Sofiya’s own journey, create opportunities for empathy amongst us and refresh our understanding of how lush Black history is. She fought to see her vision fulfilled, overcoming outdated barriers that stifle the change we hope to make in our society. Work like this encourages new growth and conversation, which we know is a grand beginning not only for our communities but for Sofiya Ballin.

Written and Edited by Kate Feher

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kris Mendoza: So how long have you been writing? Can you give me a little bit of background on your work?

Sofiya Ballin: Growing up, acting was always my passion and my love. I was able to stay involved in drama by taking acting classes but sort of moved that creativity to the back of my mind because, as a child of immigrants, there was an expectation to gear toward becoming a doctor or lawyer. But I did start writing poetry in high school as an outlet when I was being picked on and that medium stuck for me. I joined the Newspaper Club and garnered a friend group that supported what I was doing: kinda trying to figure out why we think the way we do and using journalism as the method to explore and investigate that.

I went to Temple University, majored in journalism, wrote for a local music magazine, ran a blog for Huffington Post, and freelanced here and there while going to school. I was interning at the Daily News when I got hired by The Philadelphia Inquirer. It’s funny though, I actually cried my first day because, as much as I love reporting, I still didn’t know if it was what I wanted. It felt a little stuck behind a desk and not as creative as I wanted to be. Despite being worried that I’d get too comfortable, I stayed with the Inquirer, and benefitted from a whirlwind of experiences. I got to interview everyone from Tyler Perry to Whoopi Goldberg and Tamron Hall. And of course, while I was there, I started one of my most important projects centered on Black History.

Essentially, I was asked by my editors to produce a few write-ups for Black History Month . I just remember it centering on the same figures we typically discuss around February, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, etc. These people are all prolific. But part of me was like, “Really?”

Kris Mendoza: This is stuff we learned 20 years ago in school, right? That’s nothing new.

Sofiya Ballin: Exactly, right? Black history is treated a lot like the plastic Christmas tree you have in your basement that you just dust off like, “Oh, it’s Christmas.” But what I know about Black history and Black culture is so vibrant and so colorful. I said to myself, “You know what? This year I’ll do it their way. But next year, I’ll do it differently…” And that eventually became Black History Untold.

I got inspired by my own experience growing up in a Jamaican household where I was learning so much about Black American history, African history, and Caribbean history. And then when I went to school, I wasn’t getting that. I was getting those same four or five figures, right? It wasn’t as comprehensive, and I was seeing the impact of that on students and especially Black students and how they saw themselves. How does it impact your psyche when you’re taught that your legacy, your lineage began in shackles?

I realize the impact of losing parts of your history. It affects what you know about yourself, how you view yourself, and your level of confidence, especially as a Black person in this world. How does a queer Black kid feel like they’re seen and accepted if they don’t know about Bayard Rustin, who wasn’t mainstream news coverage until now. He was a queer civil rights leader working alongside Martin Luther King?

So that next year, I decided to interview Black people, and investigate their untold Black history. I think there have been many half-truths spread in schools, but we learn it outside in our communities and from our families by hearing the personal histories that changed them. We live in a very anti-Black world. And then this is a very anti-Black country, where every day you’re told overtly or covertly, that you’re not good enough, that you’re a criminal, that you’re too much. We are consistently told these lies about ourselves. So I wanted Black people to share the stories that changed how they viewed themselves, and how it got them where they are.

Kris Mendoza: Where did you start looking for those stories?

Sofiya Ballin: So I put together a dream list, and pitched it to the Philadelphia Inquirer, and they loved it. We kept it Philly specific with a mix of celebrities like Jazmine Sullivan and Marc Lamont Hill and also everyday dope people. I don’t know if you know the actor and activist Jesse Williams..

Kris Mendoza: Yeah, I do.

Sofiya Ballin: A lot of people don’t know he went to Temple and he taught in Philadelphia schools, so he was perfect. I said, oh Black Thought, it’d be great to have him…. and all of these people said yes! Black Thought talked about reading Cheikh Anta Diop’s work and realizing, “I don’t come from a ‘dark continent’. I come from a continent where math and science was innovated.” Jazmine Sullivan talked about Negro Spirituals and how the messaging and music impacts her, not only as a singer but as a songwriter, to be intentional about the messaging she puts in her music.

Kris Mendoza: That’s inspiring, is there a repository where all these exist?

Sofiya Ballin: You can find the independent installments at blkhistoryuntold.com. Those first two installments would be on Philly.com. That year I produced it with The Philadelphia Inquirer and it had a great response. I was getting letters from the penitentiary to the nursing home. Second year, I introduced themes… I did it through the lens of Black joy. That’s when I had Malcolm Jenkins, a former Philadelphia Eagle, and Sonia Sanchez.

At the time, this was 2016, I was one of the few young Black reporters at The Inquirer. I had to compromise, ask for permission, explain things, and create a vision that, to me, didn’t fit how I wanted it to be or how I, as a Black person, felt that Black people would want to be depicted. I wanted to get out from under the restrictions and focus on the work, so I aimed to introduce film and produce independently down the line. I think film is so incredible, just capturing the emotional attachment we have with our history and our identity. It’s so sacred.

A lot of these revelations and these interviews are very emotional, and I wanted to capture that and show the beauty of that. There are so many times when I’m interviewing people, and hear, “For the first time I saw myself as someone to be revered – For the first time, I saw myself, my people, in a different light – For the first time I feel like I have a better sense of who I am.”

Kris Mendoza: It’s interesting you say that, right? Because some of these people, they’re already celebrities, and influencers and politicians in the limelight. So for them to share those moments for the first time is very telling as to who’s controlling the narrative and what’s out there; not only for the general public, but for fellow Black folk to consume. It’s very important work, what you created, can you tell us about getting it to video?

Sofiya Ballin: So after the second installment in 2018, as the project began winning awards, the newsroom became more supportive of the project and wanted to plan for the next year… And I said, “I quit.”

Kris Mendoza: What did that feel like?

Sofiya Ballin: It was the scariest, boldest thing I’ve ever done, but I wanted to protect the project. Also, I was growing, myself. I wanted to introduce video work, and that wasn’t where The Inquirer was at that time. I managed, by the grace of God, to produce the project independently, still as portraits and text but without the salary I had, and fully self-funded.

For my second independent installment, I linked up with the Brooklyn Nets to do a New York specific series. It was so wild. I got an email at 5 am.. And when I tell you, I read this and I thought I was going delusional. It was an email from the former CMO Elizabeth Brooks, writing to say she has been googling untold Black history, and wanted to tell Black History in a more intentional way. Similar to the Christmas tree analogy, she didn’t want it to just be the same thing, every year.

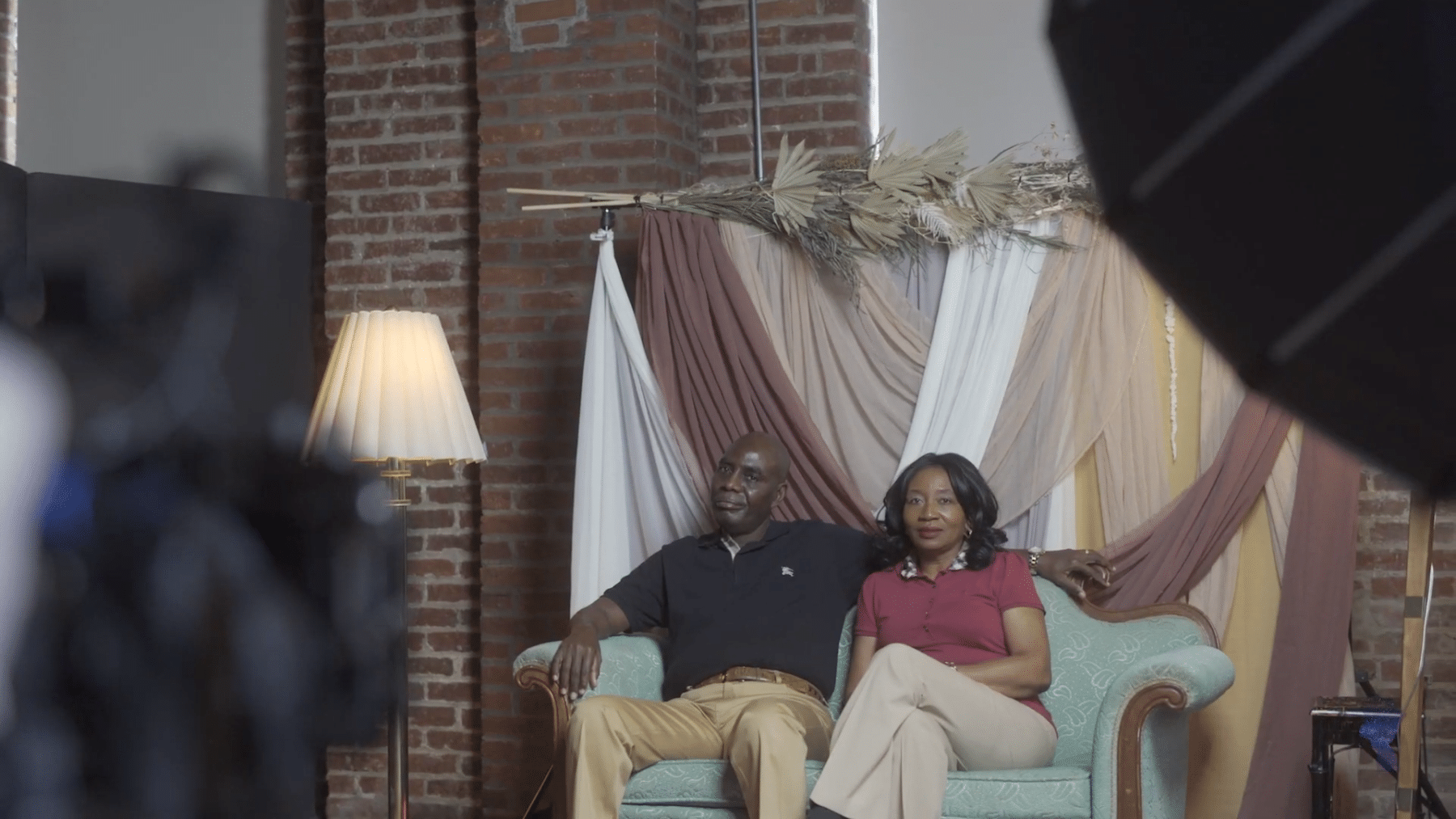

The Brooklyn Nets had the capital for me to bring on a photographer I really admired, Joshua Kissi, who then brought on a DP, Emmanuel Afolabi, who I now still have a working relationship with. And once I saw the stories expressed with emotion, through music and video, I couldn’t go back. I think the medium just complemented the project so beautifully and the audience was able to connect better.

So that’s how I got into the film industry – I had no experience or academic background in film production. It was a challenge. I had a larger team of people behind the project at The Inquirer, a 200 year old company with wide reach and resources and when I left, it was just my photographer, myself, and my friend (Temi Oyelola) was a graphic designer. As the project gained more support, I started slowly building my team up to 13 people. I learned how to produce and direct, made some expensive mistakes but I also know I have great instincts. I think that it’s what I’ve always wanted to do. It’s really, really beautiful work.

Kris Mendoza: Hearing about your trajectory is so important, because the value of storytelling – whether you’re writing for a newspaper or teasing out for video – is preserving the voice and experience of a person. A large part of Project Forte is telling your story as it connects to the ones you are working to tell, like every story is important and adds to the fuller understanding of the human experience.

Sofiya Ballin: Yes, sure the project has some household names, but I’ve also had everyday people. It’s important to treat the story as valid no matter what your tax bracket is. No matter what your visibility level is, the purpose is to show that though we are different we also share similarities that are part of the Black/African experience.

It also helped that we were a young Black crew, and I do think people felt more comfortable sharing their stories fully in that space.

Kris Mendoza: I’m glad you bring that up because there’s a question, not only around which stories are being told, but who is qualified to tell them. There’s no shortage of Black people, Asian people, or Brown people in this field, they’re only lost in the sea of the status quo, which just so happens to be very White-male driven, not even in an anti-White or anti-White-male approach. It’s present in examples of big budget Hollywood films coming out about Asian experiences: the cast may be billed as an all-Asian crew and maybe it’s filmed in Asia, but when the director at the top is “someone-Goldberg” it seems like they completely missed the point. What if Do the Right Thing was made by a White director and not by Spike Lee, it’d be completely different, right?

There’s a respectable way to tell stories of other cultures without having to be in that culture, so I’m not saying these films fail to make a difference, but I’d certainly like to see change reach the more powerful positions.

Sofiya Ballin: Yeah, I’m always shocked whenever I see these documentaries with “White hipster guys” going to Haiti or Thailand-

Kris Mendoza: “White Savior” tropes

Sofiya Ballin: Yeah. I’m like, “Why are we still doing this?” It’s upsetting. With Black History Untold there have been really powerful moments shared because our crew created such a welcoming and comfortable environment just by being Black and open to hearing the story. We interviewed a man for our Revolution Series who was wrongfully convicted of a crime and spent over 20 years behind bars. He said, “Some people get caught with drugs and all they get is a slap on the wrist, but if you or me …” And when he said “you or me” he was acknowledging us behind the scenes. That we too could have been in a similar situation. It was a simple acknowledgement that expressed that he knew we understood him. It was something really small but I took note of the fact that he felt he didn’t have to explain too much.

I can’t speak for everyone, but I’ve noticed that people hold back in certain ways if there isn’t that level of familiarity and understanding. You feel like you can’t be fully transparent. There’s a direct link between the environment and crew, to the raw, honest material we get.

Kris Mendoza: That’s a huge point.

Sofiya Ballin: When I did pitch the project the first time, I had a hard time with The Inquirer… I said I wanted all Black people on the project and they were like, “Great, and we can add white people and Asian people and have them talk about Black history…

I had to be more specific and make it an identity series. Black history impacts Black people in a very specific way, and that’s what I want to explore. For some reason, when it comes to discussing our culture and our history there’s this need to diversify it. I think it makes it feel like less of a threat to people who are caught up in their white guilt. But that’s not my business.

Historically in the press, Black people have been misrepresented or underrepresented so at the very least, let Black History Month be a time where we hear Black voices. Oftentimes, when our stories are not told by us, you can tell. It feels like an outside gaze. It can present as exoticization. The stereotypes and sensationalized versions of Black people are what’s presented. It’s an idea of us. But it’s not us. When we tell our stories, with full agency, it feels like home. For some people, these stories are home. When people watch our work, it hits a chord in them, it speaks to a place inside that only someone who is of that experience can understand.

And again, it doesn’t mean that someone who isn’t of a specific culture can’t help create something great. Especially if they’re intentional and do their research. I think that different people have different perspectives. But we have to get to the point where we have all those seats at the table, before we can really have that conversation. Because right now, only white people have had that chance in America. It’s mostly white men in the director’s chair, right?

Kris Mendoza: I dig. You mentioned the word exoticize, and I see that as connected to another issue. For corporations, it could become performative and miss the point. Having a diversity division makes a company look good, but once they push all our people of color to the forefront and take all their photos, posting everywhere… Will it continue every day or will it become another Pride Month or Black History Month? Will this behavior be sealed off into the realm of “special occasion” which we forget during the “normal” day?

Is it the lesser of two evils, to see it as performance and accept it anyway because of the good it still does?

Sofiya Ballin: That was a big motivator for my project, because the way we celebrated Black History Month, felt very much like, “Oh, the time has come. So let’s just put this up so the coloreds can be happy.” It doesn’t feel intentional.

Kris Mendoza: It becomes a Hallmark holiday.

Sofiya Ballin: Yeah, it doesn’t feel real. It doesn’t feel personal. And therefore, it defeats the purpose of helping others learn what really happened in this country and is still happening. Personally, I don’t do something just to do it. I’m very intentional about every decision that I make. And when you talked about performative actions and the lesser two evils, it reminds me of something Martin Luther King said, “It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me, but it can keep him from lynching me, and I think that’s pretty important.”

Sometimes, unfortunately, it becomes this thing where you have to mandate it before it becomes natural for future generations. I still think in many ways we’re in a place where inclusivity has to be mandated and is treated as an obligation at many companies. Something I heard in the journalism world a lot when people were talking about diversity, I’d hear “We can’t find them. We can’t find them.”

Kris Mendoza: Like there’s not enough?

Sofiya Ballin: “There’s not enough!” (they say) And yet I know so many of them! And they are so ridiculously talented, right? And overqualified!

A lot of these newsrooms can feel like a white boys’ club. And I think that people just look for people with backgrounds like theirs. What J school did you go to? Or what film school did you go to? Instead of realizing one, not everybody has all those resources…

Kris Mendoza: It becomes very homogenous very quickly if you’re not trying.

Sofiya Ballin: Yeah. One: not everyone has access to those universities, to those networks. And two: culturally, different people have told stories and passed down history in different ways, you know what I mean? And just because it may not be an important story to you or it’s not told in the way you’re used to, doesn’t mean it’s not a story within a community or that it’s not told well. Space needs to be made for that.

Kris Mendoza: Exactly. Let’s transition into some of the stuff you’re working on now and what’s next for you. I read your bio and loved that line – a dose of trap and a sprinkle of Black girl magic. We’ve talked a lot about your project and your approach to winning space for Black people, but you have not once really mentioned even being a woman in the midst of all this. What’s that extra layer like? There’s a quote I’ve seen a lot recently, stating “The Black woman is the most disrespected person in society.” Can you unpack how that relates to you and how does that reflect in your work?

Sofiya Ballin: That’s such a deep, deep question. And that’s a Malcolm X quote.I think that I’ve realized more as I’ve gotten older, through the many ways that I am treated, that there’s a sensitivity growing within me over this. Especially when it comes to directing. That is the big one, because not everyone takes well to a woman leading.

Kris Mendoza: Black or not, just women in general.

Sofiya Ballin: Women in general. And being a Black woman adds an extra layer. I have to get myself out of it and remind myself, “Sofiya you can’t be mousy. When you want something done, say it… be firm about it.” But I have such a great team because they encourage me. My camera ops, Lou Peluyera , who’s a good friend of mine, will be like, “Sofiya, it’s okay. You’re good at this. You know what you’re doing. Just be confident.”

And then I think when you add being a Black woman as your leader, especially on the business end, people will really try to take advantage of you. And people will really try to low ball you for your work. I have a lawyer friend who I’m constantly having to reach out to, to work with me on contracts, or to make sure I get paid because I have, in the past, done work for someone on good faith that they would pay me or pay me my worth.

So I’ve learned that doesn’t always happen, right? And I’m like, this is what I learned in my African American studies classes. This is what I’ve been writing about. But I’m living it, right? I’m actually watching people tell me they want to pay me nothing or a really low rate, but then in the next breath telling someone else they’re going to be paid more. That is disrespect.

We produced Black History Untold: Love , our 1 hour and 10 minute doc and interviewed 13 couples, and we did it in three or four days. It was a lot, but it was planned to a T. So it was very exhausting production, but also exhausting because of the mental demands of “bracing myself” sometimes for how people would combat or communicate with me… people outside of my team.

To be honest I might have to take a break this year, because it was just so much. We saw what happened May through June with George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. It pushed me that year because I was like, “People need to talk about Black love.” But also with Breonna Taylor specifically, I was reminded of this woman named Oluwatoyin Salau. She’s a Nigerian-American woman I wrote about in the Washington Post, who was kidnapped, sexually assaulted and killed. I did so much research involving how many Black women and girls are missing, it’s this trajectory of…

Kris Mendoza: It’s a pattern.

Sofiya Ballin: Yeah, it’s a pattern of erasure and disrespect. And it’s not because you don’t have a voice, but because people don’t want to listen to you. Oluwatoyin Salau said she needed help, before she was kidnapped. Breonna Taylor was killed in her home. And the reason why people kept pushing her name, is because so often when Black women and girls are killed in general and by the police, people don’t really rally around them the same. And why is that?

It’s a lot to be thrown into the understanding of this bigger picture and suddenly see my place in it, noticing how people are talking to me. I’ve become more and more sensitive to it.

Being a Black woman is an absolute gift, especially as a storyteller. Ava DuVernay has a quote about how as a Black woman you can… It’s almost like you see everything, right? I know what it’s like to be a woman, I know what it’s like to be a person of color. And that finds its way into my stories.

I wouldn’t trade being a black woman for anything. I hate the way the world treats us, I think we deserve better. We do a lot of incredible work, and we don’t get paid for it. We don’t get recognized. But I think that it’s truly been a gift to my storytelling and my life, especially the way that it’s made me really see the world. What I’ve experienced behind the scenes, I can take that and put that in my work, creating something specific to that.

Kris Mendoza: So, as you were saying in the beginning, this is where you draw your strength from. This is what motivates you. But I do see, when you talk about that Black girl magic, this is the source… It’s kind of like your blessing and your curse of what drives you, why you are so outspoken.

As an artist, and as a writer, as a filmmaker, I definitely think that identity as a Black female can certainly be a thumbprint all over your work. There’s no separating your identity from your work. No matter what, if it’s very culture focused, female focused or not, I feel like everything is very strongly through the lens of what only you can tell.

Sofiya Ballin: I think as a Black woman in this industry, in journalism and film, in any industry, shit, it’s so important to be confident in yourself. And it’s so important to trust. And I say this all the time but trust your vision and trust your voice. And it’s something that I’m still working on because the world won’t validate it, right? Even with this project in the beginning, I was told, “It’s not going to work. It’s just not.” When I left my job, the first thing one of the editors told me was, “I think this is a horrible idea.” I have to constantly push and prove my bankability, prove the value of my work.

Kris Mendoza: You’re wearing a weighted vest with everything you’re doing. A double weighted vest even – when everyone else is running.

Sofiya Ballin: Exactly, exactly, exactly. And that’s why Black women get the title of strong all the time. Because they’re carrying around that extra weighted vest. But every time someone compliments a Black woman on her strength, I’m like, “That’s a time that she’s struggled and you or someone else didn’t help carry the load.”

And that’s where I think the ally-ship comes in. And I think Black women try to do that for each other.

Kris Mendoza: Last question here, what’s next for you? What’s on the slate for Sofiya?

Sofiya Ballin: Yeah. I’m in such an interesting place entering this film world. I’ve mastered writing and I still want to keep doing this project. I’m just trying to solidify the system, if that makes sense. I think that I’ve been very integral to all of the pieces and I want to get to a point where it kind of runs itself. So for the future, I think that I’m going to be refining Black History Untold.

I’m also writing the script for a short film that I’m really passionate about. It goes into Jamaican culture and being first generation. I really am a storyteller of all the mediums. And now I think the next step is figuring out how to become an octopus, and how to do a little bit of all of them. Because that’s when I feel my happiest and that’s when I feel like I’m living my true purpose.